How Did Art and Literature Differ Between Europe and Japan?

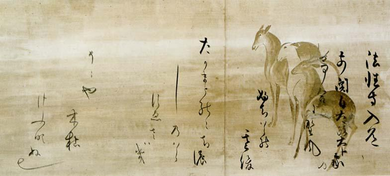

The Shin-kokin Wakashū poesy album, compiled in the early on 13th century, is considered one of the pinnacles of waka poetry.

Japan'southward medieval menstruation (the Kamakura, Nanbokuchō and Muromachi periods, and sometimes the Azuchi–Momoyama period) was a transitional period for the nation's literature. Kyoto ceased beingness the sole literary centre as important writers and readerships appeared throughout the country, and a wider multifariousness of genres and literary forms adult accordingly, such as the gunki monogatari and otogi-zōshi prose narratives, and renga linked verse, besides as diverse theatrical forms such as noh. Medieval Japanese literature tin exist broadly divided into ii periods: the early on and late middle ages, the quondam lasting roughly 150 years from the belatedly 12th to the mid-14th century, and the latter until the end of the 16th century.

The early heart ages saw a continuation of the literary trends of the classical period, with courtroom fiction (monogatari) standing to exist written, and composition of waka poetry reaching new heights in the age of the Shin-kokin Wakashū, an anthology compiled by Fujiwara no Teika and others on the order of Emperor Go-Toba. One new genre of that emerged in this period was the gunki monogatari, or war tale, of which the representative example of The Tale of the Heike, a dramatic retelling of the events of the wars between the Minamoto and Taira clans. Apart from these heroic tales, several other historical and quasi-historical works were produced in this period, including Mizu Kagami and the Gukanshō. Essays called zuihitsu came to prominence with Hōjōki by Kamo no Chōmei and Tsurezuregusa by Kenkō. Japanese Buddhism also underwent a reform during this menses, with several important new sects being established, with the founders of these sects—nearly famously Dōgen, Shinran, and Nichiren—writing numerous treatises expounding their interpretation of Buddhist doctrine. Writing in classical Chinese, with varying degrees of literary merit and varying degrees of direct influence from literature equanimous on the continent, continued to be a facet of Japanese literature as information technology had been since Japanese literature'south beginnings [ja].

The belatedly eye ages saw further shifts in literary trends. Gunki monogatari remained popular, with such famous works equally the Taiheiki and the Soga Monogatari actualization, reflecting the chaotic ceremonious war the land was experiencing at the time. The courtly fiction of early eras gave way to the otogi-zōshi, which were broader in theme and popular appeal but more often than not much shorter in length. Waka composition, which had already been in stagnation since the Shin-kokin Wakashū, connected to reject, but this gave way to new poetic forms such as renga and its variant haikai no renga (a precursor to the afterwards haiku). The performing arts flourished during the late medieval period, the noh theatre and its more informal cousin kyōgen being the best-known genres. Folk songs and religious and secular tales were collects in a number of anthologies, and travel literature, which had been growing in popularity throughout the medieval menses, became more and more commonplace. During the tardily 16th century, Christian missionaries and their Japanese converts produced the commencement Japanese translations of European works. Isoho Monogatari, a translation of Aesop'southward Fables, remained in apportionment even after the country largely airtight itself off to the w during the Edo period.

Overview [edit]

Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199) ushered in Nihon's medieval catamenia with his establishment of a war machine government in eastern Japan.

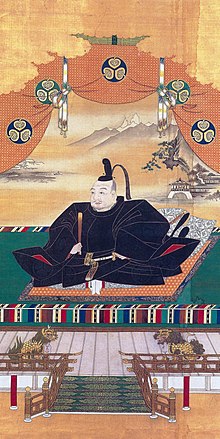

Japan'southward medieval period lasted roughly 400 years, from Minamoto no Yoritomo'due south institution of the Kamakura shogunate and existence named shōgun in the 3rd twelvemonth of the Kenkyū era (1192) to Tokugawa Ieyasu'south establishment of the Edo shogunate in Keichō 8 (1603) following the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 that began the Edo period.[1] This menstruation, based on the centres of political power, is usually divided into the Kamakura, Nanbokuchō (or Yoshino), Muromachi and Azuchi–Momoyama periods, and is also referred to simply every bit the Kamakura-Muromachi menstruum.[1] The outset date of this menstruum has likewise been taken as being effectually 1156 (the Hōgen rebellion) or 1221 (the Jōkyū rebellion), with the Azuchi–Momoyama flow as well sometimes beingness taken equally part of the early on modern period, with the medieval period ending at Oda Nobunaga's entry to the capital in Eiroku xi (1568) or the end of the Ashikaga regime in Tenshō one (1573).[1]

The institution of the Edo shogunate by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) is commonly taken as the cease of Nippon's medieval catamenia and the beginning of the early modernistic period.

The period is characterized by war, beginning with the Genpei War and ending with the Battle of Sekigahara, with other conflicts such as the Jōkyū rebellion, the state of war betwixt the northern and southern courts and the Ōnin State of war (1467–1477), culminating in the unabridged country erupting in state of war during the Sengoku menstruation.[1] The social order was disrupted equally a result of these conflicts, with changes to society in full general and, naturally, shifts in literary styles and tastes.[ane] The philosophy of impermanence (無常 mujō) became pervasive, with many seeking conservancy, both concrete and spiritual, in religion, specifically Buddhism.[1]

Aesthetic ideals [edit]

The bones ideal that informed aesthetic tastes in this period is known every bit yūgen (roughly meaning "mystery" or "depth"), along with other concepts such as ushin (有心, literally "possessing heart", the more "weighty" or "serious" poetry, as opposed to games) and yōen (妖艶, literally "ethereal dazzler").[1] These ideals shunned realism, representing a spirit of l'fine art pour 50'fine art and aiming to plunge the reader into an "platonic" world, and were in accord with the ideals of Buddhist monastic seclusion (出家遁世 shukke-tonsei).[i] What exactly constituted yūgen differed throughout its history, and the diverse literary genres it influenced include waka ("Japanese poetry", meaning poetry in vernacular Japanese, typically in a 5-7-5-7-vii metre), renga ("linked poesy") and the noh theatre.[1]

Afterwards developments include en (艶, literally "lustre" or "polish"), hie (ひえ) and sabi (roughly "stillness" or "attenuation"), connecting to the literature of Japan'south early mod period.[one] Translator and literary historian Donald Keene discusses both yūgen and hie (which he translated "chill") as concepts shared by the quintessentially medieval fine art forms of renga and noh.[two] He describes sabi as having been "used to advise the unobtrusive, unassertive dazzler that was the ideal of Japanese poets, peculiarly during the turbulent decades of the Japanese middle ages",[3] and states that it first came to prominence around the fourth dimension of the Shin-kokin Wakashū.[4]

At that place was, however, a concurrent trend toward a form of realism in medieval developments on the concept of okashi (をかし; "bright", "happy", "charming", "humorous" or "brilliant").[one] Authors began to attempt to reflect reality in social club satirize social conditions, or for simple enjoyment.[ane]

[edit]

Medieval Japanese literature is most often associated with members of the warrior course, religious figures and hermits (隠者 inja), but the dignity maintained a degree of their former prestige and occupied an of import position in literary circles.[i] This was peculiarly true in the early center ages (i.due east., the Kamakura menstruation), when court literature still carried the high pedigree of earlier eras, while monks, recluses and warriors took an increasingly prominent role in later centuries.[1] Furthermore, at the very finish of the medieval catamenia (i.e., the Azuchi–Momoyama period), urban (chōnin) literature began to announced.[1] Every bit a outcome, the medieval period was the fourth dimension when the literature of the nobility became a truly "national" Japanese literature.[1]

Developments in the performing arts allowed for big groups of people to appreciate literature on a broader level than earlier.[ane] As the social classes that had previously supported the arts fell away, new groups stepped in equally both creators and audiences for literary works.[one] These conditions encouraged the growth of a literature that was more visual and auditory than the literature of Japanese classical flow.[1] This is truthful of performing arts similar noh and traditional trip the light fantastic toe, but also includes such genres as the emakimono, pic scrolls that combined words and images, and due east-toki, which conveyed tales and Buddhist parables via images.[one]

The centre of civilisation continued to be the capital letter in Kyoto, but other areas such every bit Ise and Kamakura became increasingly prominent as literary centres.[1]

Literature of the early medieval period [edit]

Historical background of the early medieval menstruum [edit]

The early on medieval period covers the time betwixt the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate and the shogunate's collapse roughly 140 years later on in Genkō 3 (1333).[1] With the shogunate, who were of warrior stock, controlling the affairs of country in eastern Nippon, the aristocracy of the Heian court continued to perform express courtroom functions and attempted to preserve their aristocratic literary traditions.[1] The outset two or 3 decades, which are likewise known as the Shin-kokin period, saw a surge in interest in waka limerick and attempts to revive the traditions of the by.[one] Notwithstanding, with the failure of the Jōkyū rebellion and Emperor Go-Toba's exile to Oki Island, the courtroom lost almost all power, and the dignity became increasingly nostalgic, with the aristocratic literature of the later on Kamakura flow reflecting this.[ane]

As the warrior class was in its ascendancy, their cultural and philosophical traditions began to influence non just political but also literary developments, and while literature had been previously the sectional domain of the courtroom this catamenia saw a growth in the literature of other levels of society.[1] Narrative works such as The Tale of the Heike are an instance of this new literature.[1]

Buddhism was too in its heyday during this catamenia, with new sects such as Jōdo-shū, Nichiren-shū and Zen-shū being established, and both old and new sects fervently spreading their influence amidst the populace throughout the country.[one] In improver to Buddhist literature such every bit hōgo, the monks of this menses were especially active in all manner of literary pursuits.[1] Those who became hermits upon entering Buddhism produced a new kind of work, the zuihitsu or "essay", every bit well as fine examples of setsuwa ("tale") literature.[1] Such literature is known as hermit literature (隠者文学 inja-bungaku) or "thatched-hut literature" (草庵文学 sōan-bungaku).[1]

Overall, the literature of this period showed a strong tendency to combine the new with the old, mixing the culture of aristocrats, warriors and Buddhist monks.[one]

Early medieval waka [edit]

The waka genre of poetry saw an unprecedented level of exuberance at the beginning of the Kamakura period, with Emperor Go-Toba reopening the Waka-dokoro in Kennin one (1201).[1] Notable, and prolific, poets at the highest levels of the aristocracy included Fujiwara no Yoshitsune and his uncle, the Tendai abbot Jien.[1] At both the palace and the homes of various aristocrats, poetry gatherings (uta-kai) and competitions (uta-awase) such as the famous Roppyaku-ban Uta-awase and Sengohyaku-ban Uta-awase were held, with numerous peachy poets coming to the fore.[ane] On Go-Toba's command, Fujiwara no Teika, Fujiwara no Ietaka and others compiled a new chokusenshū (imperial waka anthology), the Shin-kokin Wakashū, which was seen as a continuation of the grand waka tradition begun 3 hundred years earlier with the Kokin Wakashū.[1] Teiji Ichiko, in his article on medieval literature for the Nihon Koten Bungaku Daijiten, calls this the final flowering of the aristocratic literature, noting its high literary value with its basis in the literary ethics of yūgen and yūshin, its emphasis on suggestiveness, and its exquisite delicacy.[ane]

The foundations for this mode of poesy were laid by Teika and his father Shunzei, not merely in their poetry only in their highly regarded works of poetic theory (karon and kagaku-sho).[1] These include Shunzei'south Korai Fūtei-shō (likewise valuable equally an exploration of the history of waka) and Teika's Maigetsu-shō and Kindai Shūka (近代秀歌).[one] Such works had a tremendous influence on later waka poets, and their philosophy of fūtei (風体, "style") has had value for Japanese aesthetics and art mostly.[5] Other works of poetic theory include those that are noted for their recording of diverse anecdotes about waka poets, including Kamo no Chōmei's Mumyō-shō .[6]

This flourishing was characteristic of the outset three or four decades of the Kamakura period, but post-obit the Jōkyū rebellion and the exile of Go-Toba, the great patron of waka, the genre went into reject.[half-dozen] Teika's son, Fujiwara no Tameie, championed simplicity in waka limerick, writing the karon work Eiga no Ittei.[6] In the generation following Tameie, the waka world became divided between schools represented by the three great houses founded by Tameie's sons: Nijō, Kyōgoku and Reizei.[6] The conservative Nijō schoolhouse, founded past Tameie'south eldest son, was the about powerful, and with the unlike schools supporting unlike political factions (namely the Daikakuji-tō and the Jimyōin-tō), there was less emphasis on poetic innovation than on in-fighting, and the genre stagnated.[vi]

The compilation of royal anthologies, though, actually became more frequent than before, with a ninth album, the Shin-chokusen Wakashū, and continuing on regularly over the following century until the sixteenth, the Shoku-goshūi Wakashū.[6] Of these viii, the but i that was compiled by a member of the Kyōgoku schoolhouse was the Gyokuyō Wakashū, compiled by Kyōgoku Tamekane, and this is considered the second best of the Kamakura anthologies after the Shin-kokin Wakashū.[6] Every other collection was compiled by a Nijō poet, and according to Ichiko there is footling of value in them.[6] However, in eastern Japan the third shōgun, Minamoto no Sanetomo, a student of Teika's, showed neat poetic skill in his personal anthology, the Kinkai Wakashū , which shows the influence of the much earlier poetry of the Human'yōshū.[6]

Overall, while poetic composition at court floundered during the Kamakura period, the courtiers continued the human activity of collecting and categorizing the poems of earlier eras, with such compilations as the Fuboku Waka-shō and the Mandai Wakashū (万代和歌集) epitomizing this nostalgic trend.[6]

Monogatari [edit]

Works of courtly fiction, or monogatari (literally "tales"), continued to exist produced by the aristocracy from the Heian period into the Kamakura period, with the early Kamakura work Mumyō-zōshi, written by a devout fan of monogatari, particularly The Tale of Genji, emphasizing literary criticism and discussing various monogatari, every bit well every bit waka anthologies and other works by the court ladies.[6] The work praises Genji and then goes on to talk over various works of courtly fiction in roughly chronological order, and is non but the sole piece of work of such literary criticism to survive from this period merely is also valuable for detailing the history of the genre.[vi]

Matsuranomiya Monogatari is the one surviving piece of work of prose fiction by Fujiwara no Teika, the greatest poet of the age.[vii]

The Fūyō Wakashū is a slightly later work that collects the waka poetry that was included in courtly fiction up to around Bun'ei 8 (1271).[6] This piece of work was compiled on the order of Emperor Kameyama's mother Ōmiya-in (the daughter of Saionji Saneuji), and shows not merely the high identify ladylike fiction had attained in the tastes of the aristocracy by this time, but the reflective/critical bent with which the genre had come to be addressed in its final years.[6] Well over a hundred monogatari announced to have been in circulation at this time, but almost all are lost.[6] Fewer than 20 survive, and of the surviving works, several such equally Sumiyoshi Monogatari, Matsuranomiya Monogatari and Iwashimizu Monogatari (石清水物語) have unusual contents.[6] Other extant monogatari of this period include Iwade Shinobu , Wagami ni Tadoru Himegimi , Koke no Koromo and Ama no Karumo (海人の刈藻).[6]

Belatedly Kamakura works of courtly fiction include Koiji Yukashiki Taishō , Sayo-goromo and Hyōbu-kyō Monogatari , and these works in item prove a very potent influence from before works, in item The Tale of Genji, in terms of construction and language.[6] Long works of courtly fiction at this fourth dimension were most all giko monogatari ("pseudo-primitive" tales, works imitative of by monogatari), and production of them largely ceased during the Nanbokuchō period.[6]

Early medieval rekishi monogatari and historical works [edit]

Works that connected the tradition of Heian rekishi monogatari ("historical tales") such as Ōkagami ("The Corking Mirror") and Ima Kagami ("The New Mirror") were written during this period.[6] Mizu Kagami ("The Water Mirror"), for example, recounts the history of Nippon betwixt the reigns of Emperor Jinmu and Emperor Ninmyō, based on historical works such equally the Fusō Ryakuki.[6] Akitsushima Monogatari (秋津島物語) attempted to recount events before Jinmu, in the age of the gods.[vi]

More serious historical works composed during this period include the Gukanshō, which describes the menstruum betwixt Emperor Jinmu and Emperor Juntoku.[6] It besides attempted to describe the reasons for historical events and the lessons to be learned from them, and unlike the historical romances beingness produced at court that reflected nostalgically on the by, the Gukanshō used history as a way to criticize present guild and provide guidance for the future.[vi] It is also noteworthy for its uncomplicated, direct language, which was a new innovation of this catamenia.[6]

Early medieval gunki monogatari [edit]

A 17th-century folding screen depicting scenes front The Tale of the Heike

The historical and court romances were a continuation of the works of the Heian period, only a new genre that built upon the foundations laid by these emerged in the Kamakura menstruation: the gunki monogatari (warrior tale), which is besides known as simply gunki, or senki monogatari.[six] The immediate predecessors of these works were kanbun chronicles composed in the Heian era such as the Shōmonki and Mutsu Waki , as well equally warrior tales included in the Konjaku Monogatari-shū.[six]

The gunki monogatari emerged in the early medieval era equally a form of pop entertainment, with the most important early works beingness the Hōgen Monogatari, the Heiji Monogatari, and The Tale of the Heike.[6] These three recounted, in lodge, the iii major conflicts that led to the rise of the warrior class at the end of the Heian menstruation. They were composed in wakan konkō-bun, a course of literary Japanese that combined the yamato-kotoba of the court romances with Chinese elements, and described fierce battles in the style of epic poetry.[half-dozen] They portrayed strong characters proactively and forcefully, in a manner that Ichiko describes equally advisable for the age of the warrior class'due south ascendancy.[half dozen] The Heike in item was widely recited by biwa-hōshi, travelling monks, usually blind, who recited the tale to the accompaniment of the biwa, and this was a very pop class of entertainment throughout the country all through the middle ages.[6]

The authors of these works are largely unknown, but they were ofttimes adapted to come across the tastes of their audiences, with court literati, Buddhist hermits, and artists of the lower classes all likely having a paw in their formation.[6] There are, consequently, a very large number of variant texts.[6] In addition to the largely unprecedented fashion in which these works were formed, they led to the ascent of the heikyoku manner of musical accompaniment.[half-dozen]

Following these iii, the Jōkyū-ki , which recounted the events of the Jōkyū rebellion, was besides compiled.[6] Together, the iv are known as the Shibu Gassen-jō (四部合戦状).[six] The Soga Monogatari, which was equanimous toward the end of this catamenia, placed its focus on heroic figures, and laid the foundations for the gunki monogatari of the Muromachi catamenia.[6]

Some gunki monogatari in this period took the form of motion picture scrolls.[6]

Early on medieval setsuwa literature [edit]

Similarly to new the innovations in the collection and categorization of waka poetry in the Kamakura menstruation, the period saw an upswing in the compilation and editing of setsuwa, or short tales and parables.[half-dozen] This included aristocratic collections such as the Kokon Chomonjū, the Kojidan and the Ima Monogatari , equally well as the Uji Shūi Monogatari, which also incorporates stories of commoners.[half dozen] Other works targeted at members of the newly ascendant warrior class had a stronger accent on disciplined learning and Confucianism, as exemplified in the Jikkinshō .[6]

Buddhist setsuwa works were meant to provide resource for sermons, and these included the Hōbutsu-shū of Taira no Yasuyori and Kamo no Chōmei'south Hosshin-shū , the Senjū-shō and Shiju Hyakuin Nenshū (私聚百因縁集).[six] Of particular note are the works of monk and compiler Mujū Dōgyō, such as Shaseki-shū and Zōdan-shū (雑談集), which mix fascinating anecdotes of everyday individuals in with Buddhist sermons.[6]

These setsuwa collections, similar those of earlier eras, compile tales of Buddhist miracles and the dignity, but works like the Kara Monogatari also comprise tales and anecdotes from China, and some include tales of commoners, showing a alter in tastes in this new era.[six]

Some works describe the origins of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines and collect tales of miracles.[8] Such works include the Kasuga Gongen Genki and the Kokawa-dera Engi , both of which are emakimono that combine words and images.[vi] These are a development of the earlier engi that were written in kanbun, but Ichiko classifies them every bit a form of setsuwa.[half-dozen]

Early medieval diaries, travel literature and essays [edit]

Ladies at court connected to write diaries as they had during the Heian catamenia, with important examples including Nakatsukasa no Naishi Nikki and Ben no Naishi Nikki .[nine] Of particular interest are diaries written by women who became nyoin (courtroom ladies) during the Taira ascendancy such as Kenshun-mon'in Chūnagon Nikki and Kenrei-mon'in Ukyō no Daibu Shū , which provide a glimpse of life backside the scenes at the palace.[nine] The latter in particular, written by Kenrei-mon'in Ukyō no Daibu who had come to court to serve Kenrei-mon'in, is focused primarily on verse that conveys her sadness and lamentation, following the downfall of the Taira clan in warfare, which shows a grapheme quite unlike from the ladies' diaries of the Heian period.[ix] Towazu-gatari, a work by Go-Fukakusain no Nijō, combines reflections on her fourth dimension serving at court with a travelogue.[9] Information technology provides a bare-faced look at the inner thoughts and desires of its author, which is rare for a work written by a woman of this period, causing Ichiko to compare it to the I novel.[9]

Literary diaries written in Japanese by men, such equally Asukai Masaari's Haru no Miyamaji (はるのみやまぢ, as well known as 飛鳥井雅有日記 Asukai Masaari Nikki) began to appear.[nine] The tradition of kanbun-nikki (diaries in classical Chinese) used to tape the day-to-day lives of the nobility also continued, of which Teika's Meigetsuki is the best-known instance.[9]

Considering of the biregional nature of government in this flow, with the courtroom in Kyoto and the shogunate in Kamakura, works describing the journey forth the Tōkaidō betwixt Kyoto and Kamakura, such every bit Kaidōki , Tōkan Kikō , and the nun Abutsu's Izayoi Nikki began to appear en masse.[ix] Kaidōki and Tōkan Kikō were written by highly educated men in wakan konkō-bun.[nine]

Takakura-in Itsukushima Gokōki (高倉院厳島御幸記) is one important case of the growing subgenre of travelogues describing pilgrimages to shrines and temples.[ix] Ryūben Hōin Saijōki (隆弁法印西上記) recounts the Tsurugaoka Hachimangū bettō Ryūben's journey to Onjō-ji and the time he spent at that place.[ix] Information technology was probable composed by ane of Ryūben's travelling companions, and is noteworthy partly for its unusual gaps in describing the journey, and for its frank portrayal of the perversity of the monks.[9]

The essay, represented by Kamo no Chōmei'due south Hōjōki, rose to prominence in this menstruation.

Works discussing the rejection of the cloth world, beginning with Saigyō at the stop of the previous era, connected to be composed in the Kamakura period.[9] These works combined verse describing the recluse life in thatched-hut retreats with magnificent essays called zuihitsu.[9] The almost important examples are Kamo no Chōmei'southward Hōjōki and Kenkō's Tsurezuregusa which were written around the very end of the Kamakura period and the start of the Nanbokuchō flow.[9] The former describes its writer'southward journey toward giving upwardly the globe, social changes, and celebrates recluse life, while the latter is a work of instruction detailing its author's inner thoughts and feelings every bit he lives in quiet seclusion.[nine] Along with the classical Pillow Volume, they are considered the archetypal Japanese zuihitsu.[ix]

Buddhist literature and songs [edit]

While many of the works described higher up accept Buddhist themes, "Buddhist literature" hither refers to a combination the writings of great monks of the diverse Japanese Buddhist sects and the collections of their sayings that were produced past their followers.[nine] These include:

- Dōgen's Shōbō Genzō and Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki, the latter of which was recorded past his disciple, Koun Ejō;[9]

- Mattōshō (末灯鈔), which collected the writings of Shinran, and Tannishō, a compilation of his teachings;[9]

- Nichiren's Kaimokushō and other works.[nine]

Many of these Buddhist writings, or hōgo, expound on deep philosophical principles, or explain the nuts of Buddhism in a simple manner that could easily be digested by the uneducated masses.[nine]

In addition to the continued production of imayō , sōka (早歌) were created in large numbers, and their lyrics survive in textual form.[9] Buddhist songs were performed every bit office of ennen , etc., and of detail note is the wasan form.[nine] Many of these wasan were supposedly created by Buddhist masters of the Heian catamenia, but the class became prominent in the Kamakura menstruum.[9] These songs were composed with the goal of educating people well-nigh Buddhism, and were widely recited effectually the state.[9] Ichiko writes that the songs themselves are moving, merely that Shinran's Sanjō Wasan and afterward songs were particularly brilliant works of Buddhist literature.[ix]

Furthermore, engi associated with famous temples, and illustrated biographies of Japanese Buddhist saints such as Kōya-daishi Gyōjō Zue (高野大師行状図絵), Hōnen-shōnin Eden (法然上人絵伝), Shinran-shōnin Eden (親鸞上人絵伝), Ippen-shōnin Eden , continued to be produced during the Kamakura menstruum and well into the Nanbokuchō period.[ix] Ichiko categorizes these as examples of the Buddhist literature of this period.[9]

Literature of the late medieval period [edit]

Historical background of the late medieval period [edit]

Emperor Go-Daigo brought an cease to the Kamakura period by overthrowing the Kamakura shogunate and briefly restoring majestic rule. When this failed, he and his followers established a court in Yoshino, south of the upper-case letter.

The tardily medieval period covers the roughly 270 years that, by conventional Japanese historiography, are classified as the Nanbokuchō (1333–1392), Muromachi (1392–1573) and Azuchi–Momoyama (1573–1600) periods.[ix] The conflict between the northern and southern courts in the Nanbokuchō menses, and the frequent civil wars in the Muromachi period, caused massive social upheaval in this flow, with the nobility (who were already in turn down) losing virtually all of their old prestige, and lower classes moving upwards to take their identify.[9] In item, the high-level members of the warrior course took over from the elite as the custodians of civilisation.[9]

Ashikaga Takauji initially supported Emperor Go-Daigo before turning on him and establishing the Muromachi shogunate, which supported the northern court in Kyoto.

The literature of this menses was created past nobles, warriors, and hermits and artists of the lower classes.[9] The popular literature and entertainment, which had previously been of little consequence, came into the limelight during this time.[9] The noh theatre came nether the protection and sponsorship of the warrior class, with Kan'ami and his son Zeami bringing it to new artistic heights, while Nijō Yoshimoto and lower-class renga (linked poesy) masters formalized and popularized that class.[9]

This is the point when "ancient" literature came to an end and was replaced with literature more representative of the early modern catamenia.[ix] This results in some caste of schizophrenia in the literature of this period, as contradictory elements are mixed freely.[nine] Deep and serious literature was combined with lite and humorous elements, which is a noteworthy characteristic of tardily medieval literature.[ix] Noh and its comic counterpart kyōgen is the standard case of this phenomenon, merely renga had haikai, waka had its kyōka and kanshi (poetry in Classical Chinese) had its kyōshi.[ix] Monogatari-zōshi composed during this period combined the enlightened of the serious monogatari with characteristics of humorous anecdotes.[nine]

Literature characterized by wabi-sabi was valued during this period of cluttered warfare.[ix] Commentary on and collation of the classics also came to the fore, with the "hidden traditions" of Kokinshū interpretation (kokin-denju ) beginning.[9] Furthermore, it was during this period that the classical Japanese literary tradition ceased to exist the exclusive prerogative of the aristocracy, and passed into the easily of scholarly-minded warriors and hermits.[nine] Ichijō Kaneyoshi and Sanjōnishi Sanetaka were noteworthy scholars of aristocratic origins, and in add-on to writing commentaries such aloof scholars examined and compared a large volume of manuscripts.[9] This opening upwardly to the general populace of classical literature was too advanced past hermit renga masters such as Sōgi.[9]

Ichiko notes that while this reverence for the literature of the past was of import, it is also a highly noteworthy feature of this period that new genres and forms, unlike those of before eras, prevailed.[9] He also emphasizes that fifty-fifty though this was a period of encarmine warfare and tragedy, the literature is oftentimes lively and bright, a tendency that continued into the early modern menstruum.[9]

Literature in Chinese [edit]

Classical Chinese (kanbun) literature of the Heian period had been the domain of aloof men, but equally the aristocracy fell from prominence writing in Chinese became more closely associated with Zen Buddhist monks.[nine] Zen monks travelling back and forth between Nippon and China brought with them the writings of Song and Yuan Cathay,[10] and writing in Chinese past Japanese authors experienced something of a renaissance.[xi]

The Chinese literature produced during this period is known equally the literature of the Five Mountains because of its close association with the monks of the 5 Mountain Organization.[12] The founder of the lineage was Yishan Yining (Issan Ichinei in Japanese), an immigrant from Yuan China,[12] and his disciples included Kokan Shiren,[13] Sesson Yūbai,[14] Musō Soseki[14] and others;[fourteen] these monks planted the seeds of the 5 Mountains literary tradition.[15] Kokan's Genkō Shakusho is an important work of this menses.[13] Ichiko remarks that while Chūgan Engetsu likewise created excellent writings at this time, it was Musō's disciples Gidō Shūshin and Zekkai Chūshin who brought the literature of the Five Mountains to its zenith.[13] Keene calls the latter two "masters of Chinese poetry",[16] describing Zekkai as "the greatest of the Five Mountains poets".[16]

Musō and Gidō in item had the ear of powerful members of the military grade, to whom they acted as cultural and spiritual tutors.[13] The tradition continued to flourish into the Muromachi period, when it came under the protection of the shogunate, only this led to its developing a tendency toward sycophancy, and while there continued to be exceptional individuals like Ikkyū Sōjun, this period showed a general tendency toward stagnation and degradation.[13] Withal, Ichiko notes, the literature of the Five Mountains had a profound impact on the cultural and artistic development of the Nanbokuchō period.[13]

Late medieval waka [edit]

Iv imperial anthologies were compiled during the Nanbokuchō period: iii by the Nijō schoolhouse and 1, the Fūga Wakashū, by the Kyōgoku school.[xiii] The latter was directly compiled by retired emperor Kōgon, and has the second greatest number of Kyōgoku poems after the Gyokuyō Wakashū.[13] The Shin'yō Wakashū, a quasi-chokusenshū compiled past Prince Munenaga, collects the works of the emperors and retainers of the Southern Court.[13]

In the Muromachi period, the waka composed by the nobility connected to stagnate, and after Asukai Masayo compiled the Shinshoku-kokin Wakashū, the xx-first regal anthology, the age of court waka was at its terminate.[13]

The most important waka poets of this menstruum were not courtiers simply monks, hermits, and warriors. Examples of prominent monk-poets are the Nijō poet Ton'a in the Nanbokuchō period and Shōtetsu (who wrote the book of poetic theory Shōtetsu Monogatari ) and Shinkei (who was also a noted renga chief) in the Muromachi menstruation.[thirteen] Of import waka poets of the samurai class include Imagawa Ryōshun in the early period, Tō Tsuneyori (said to exist the founder of the kokin-denju tradition) and others toward the middle of this menstruation, and Hosokawa Yūsai at the very end of the middle ages.[13] Yūsai carried the waka tradition on into the early on modernistic period, an human action whose significance, according to Ichiko, should not exist underestimated.[13]

Renga [edit]

Nijō Yoshimoto is credited with securing the status of renga as an important literary exercise.[17]

Linked verse, or renga, took the identify of waka as the dominant poetic form during this period.[thirteen] Renga, or more specifically chō-renga (長連歌), emphasized wit and change, and was practiced in earlier times past both the nobility and commoners, but during the Nanbokuchō menstruation Nijō Yoshimoto organized gatherings of both nobles and commoners and with the assistance of hermits similar Kyūsei was able to formalize the renga tradition and compile the first true renga anthology, the Tsukuba-shū.[13] Yoshimoto likewise composed important books of renga theory such every bit Renri Hishō and Tsukuba Mondō (筑波問答).[13]

Afterward came notable poets like Bontōan, but renga went into a brief period of stagnation until the Eikyō era (1429–1441), when the favour of the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshinori led to its beingness rejuvenated.[13] The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林の七賢), including such masters equally Sōzei and Shinkei were at their tiptop during this flow.[13] Shinkei, who was also a prominent waka poet, wrote works of waka and renga theory such as Sasame-goto and Hitori-goto.[13] Sōgi, who was active from roughly the fourth dimension of the Ōnin State of war, built on these developments and helped renga to reach its highest point.[13] With Kensai he compiled the Shinsen Tsukuba-shū, and with his disciples Shōhaku and Sōchō create renga masterpieces such as Minase Sangin Nannin Hyakuin (水無瀬三吟何人百韻) and Yuyama Sangin (湯山三吟).[13]

Sōgi'south disciples Sōchō, Sōseki (ja), Sōboku and other'due south carried on his legacy, pedagogy others and continuing the glory days of the genre.[xiii] The most of import renga master of the stop of this menstruum was Satomura Jōha, who wrote Renga Shihō-shō (連歌至宝抄).[thirteen] He continued the do of expanding renga to the masses, with his family (the Satomura clan) continuing to play a central function in the renga earth into the Edo menstruation.[13] Under his influence, renga became fixed, causing it to stagnate, and leading to the increased popularity of haikai no renga.[xiii]

Haikai had been pop even in the gold age of renga, but went on the rise starting time with Chikuba Kyōgin-shū (竹馬狂吟集), the Ise priest Arakida Moritake's Haikai no Renga Dokugin Senku (俳諧之連歌独吟千句, likewise known equally Moritake Senku 守武千句) and Yamazaki Sōkan's Inu Tsukuba-shū (Haikai Renga-shō 俳諧連歌抄) in the late Muromachi flow.[thirteen] Haikai developed from renga at roughly the same time as kyōka developed from waka.[13] Some haikai, according to Ichiko, ventured also far into absurdity, but they tapped into the pop spirit of the Japanese masses, and laid the groundwork for the major developments of the form in the early modern period.[xiii]

Monogatari-zōshi [edit]

The giko-monogatari of the earlier menses largely ceased during the Nanbokuchō period, and an incredibly big number of shorter works known every bit monogatari-zōshi (more commonly called otogi-zōshi, a name that was practical later) were created.[13] Many of them are unsophisticated and childish, and were written for a much broader audience than the before tale literature, which had been written by and for the elite exclusively.[thirteen] Every bit a consequence, they cover a much broader range of topics, and were written not but by nobles just past warriors, monks, hermits and urbanites.[13]

Utatane Sōshi is a noted example of the "aloof" otogi-zōshi.[18]

Of the works that continued the courtly tradition, some (such as Wakakusa Monogatari) told romantic love stories and some (such as Iwaya no Sōshi) independent stories of unfortunate stepchildren.[13] Among those near members of the warrior class, some (such as Shutendōji) drew upon gunki monogatari and heroic legends of monster-slayers, some (such as Onzōshi Shima-watari) built legends of warriors, and others (such as Muramachi Monogatari and Akimichi) told of chaos between rival houses and revenge.[13] A very large number of them are virtually religious themes, reflecting the rise of pop Buddhism during this period.[13] Some of these works (such as Aki no Yo no Naga Monogatari) described monastic life, some (such equally Sannin Hōshi) expounded the virtues of seclusion, some (such equally Kumano no Honji) elaborate on the origins of temples and shrines in light of the concept of honji suijaku ("original substances manifest their traces", the concept that the gods of Shinto are Japanese manifestations of Buddhist deities[19]), and some (such every bit Eshin-sōzu Monogatari) are biographies of Buddhist saints.[13]

In addition to the above works most nobles, warriors and monks, there are also a number of works in which the protagonists are farmers and urban commoners, known every bit risshin-shusse mono (立身出世物, "tales of rising upwards in the world") and shūgi-mono (祝儀物).[13] Examples of the former include Bunshō-zōshi (文正草子) and examples of the latter include Tsuru-Kame Monogatari (鶴亀物語).[13] A number of these works are based on popular folk-tales, and reflect themes of gekokujō and the lively activity of the lower classes.[xiii] Several feature settings outside Nihon, including the engi-mono of the early flow and such works as Nijūshi-kō (二十四孝) and Hōman-chōja (宝満長者).[13]

A number of works, called irui-mono (異類物) or gijin-shōsetsu (擬人小説, "personification novels"), include anthropomorphized plants and animals, and these appear to have been very popular among readers of the day.[13] Examples of this group include state of war stories like Aro Gassen Monogatari (鴉鷺合戦物語, lit. "The Tale of the Battle of the Crow and the Heron"), love stories like Sakura-Ume no Sōshi (桜梅草子), and tales of spiritual awakening and living in monastic seclusion such as Suzume no Hosshin (雀の発心), while some, such equally Nezumi no Sōshi (鼠の草子), portray romance and/or wedlock between humans and anthropomorphized animals, and such works were widely disseminated.[13] These works, along with tales of slaying monsters (怪物退治談 kaibutsu-taiji tan), announced to have been pop in an age when weird and creepy tales (怪談 kaidan (literature) and 奇談 kidan) proliferated.[13]

The short prose fiction of this era, as elaborated above, differed drastically from the courtly fiction of early ages in its variety.[xiii] More than 500 were written, and many come downwardly to u.s. in manuscript copies that include cute coloured illustrations.[13] It is believed that these works were read aloud to an audition, or were enjoyed past readers of varying degrees of literacy with the help of the pictures.[thirteen] They represent a transition between the courtly fiction of earlier times to the novels of the early modern period.

Late medieval rekishi monogatari and historical works [edit]

Kitabatake Chikafusa wrote one of the most important historical works of this menses.

The piece of work Masukagami ("The Clear Mirror"), a historical tale of the kind discussed to a higher place, was created in the Nanbokuchō period.[13] It was the final of the "mirrors" (鏡物 kagami-mono) of Japanese history, and portrays the history, primarily of the imperial family, of the menstruum between the emperors Become-Toba and Go-Daigo.[13] Ichiko writes that it is a nostalgic work that emphasizes continuity from the past, and is lacking in new flavour, but that amongst the "mirrors" the quality of its Japanese prose is 2d just to the Ōkagami.[thirteen]

Other works, such every bit the Baishōron , straddle the border between the courtly "mirrors" and the gunki monogatari;[13] the about noteworthy work of this period, though, is Kitabatake Chikafusa's Jinnō Shōtōki, which describes the succession of the emperors beginning in the Age of the Gods.[20] Similarly to the Gukanshō, it includes not only a dry narration of historical events but a degree of estimation on the part of its author, with the primary motive being to demonstrate how the "correct" succession has followed down to the nowadays day.[21] Ichiko notes the grave and solemn linguistic communication and tensity of the content of this piece of work of historical scholarship, which was written during a time of abiding warfare.[21]

Belatedly medieval gunki monogatari [edit]

The most outstanding tale of military conflict of this menses is the Taiheiki,[21] a massive work noted not simply for its value equally a historical relate of the conflict between the Northern and Southern courts but for its literary quality.[22] It is written in a highly Sinicized wakan konkō-bun, and lacks the lyricism of The Tale of the Heike, being plainly meant more than every bit a piece of work to be read than sung to an audience.[21] Information technology is infused with a sense of Confucian ethics and laments the last days, and its criticism of the rulers gives it a new flair.[21] Ichiko calls it 2nd just to the Heike as a masterpiece of the gunki monogatari genre.[21] The work'south title, meaning "Record of Great Peace", has been interpreted variously every bit satire or irony,[23] referring to the "bang-up pacification" that its heroes attempt to implement, and expressing a sincere hope that, following the finish of the vehement events it describes, peace would finally render to Japan.[22]

Peace did not return, still, and, conveying over into the Muromachi period, war connected near without cease.[21] Tales of martial escapades in this flow include the Meitokuki , the Ōninki and the Yūki Senjō Monogatari (結城戦場物語).[21] Ichiko notes that while each of these works have unique characteristics, they tend to follow a formula, recounting the (more often than not modest-scale) existent-world skirmishes that inspired them in a blasé fashion and lacking the masterful quality of the Heike or Taiheiki.[21] The Tenshōki (天正記), a collective name for the works Ōmura Yūko, records the exploits of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[21] It and other works of this period, which Ichiko calls "quasi-gunki monogotari" (準軍記物語), portray not large-scale conflicts with multiple heroes, but function more as biographical works of a single general.[21] This adjunct genre includes tales such every bit the Soga Monogatari, which recounts the conflict of the Soga brothers, and the Gikeiki, which is focused on the life of the hero Minamoto no Yoshitsune.[21] Ichiko notes that this kind of work broke the "deadlock" in the military tales and (particularly in the case of the Gikeiki) had a tremendous influence on the literature of afterward times.[21]

Belatedly medieval setsuwa literature [edit]

Setsuwa anthologies were plainly not as pop in the tardily medieval period as they had been earlier,[21] with writers actually favouring the creation of standalone setsuwa works.[21] In the Nanbokuchō menstruation,[a] there was the Yoshino Shūi , a collection of uta monogatari-type setsuwa nigh poets tied to the Southern Court,[21] but more noteworthy in Ichiko's view is the Agui Religious Instruction Community's Shintō-shū, believed to exist the origin of the shōdō , a genre of pop literature expounding Buddhist principles.[21] The Shintō-shū contains l stories,[21] more often than not honji suijaku-based works describing the origins of the gods of Shintō.[21] There is a focus in the piece of work on the Kantō region, and on divinities with the championship myōjin,[21] and information technology contains several setsuwa-type works, such as "The Tale of the Kumano Incarnation" (熊野権現事 Kumano-gongen no koto) and "The Tale of the Mishima Thou Divinity" (三島大明神事 Mishima-daimyōjin no koto) in the vein of setsuwa-jōruri and otogi-zōshi.[21]

Going into the Muromachi catamenia, works such as the Sangoku Denki (三国伝記) and Gentō (玄棟) and Ichijō Kaneyoshi'southward Tōsai Zuihitsu are examples of setsuwa-type literature.[21] A variant on the setsuwa anthology that developed in this period is represented past such works as Shiteki Mondō (塵滴問答) and Hachiman Gutōkun , which accept the form of dialogues that recount the origins of things.[21] Forth with the Ainōshō , an encyclopedic piece of work compiled around this fourth dimension, these stories probably appealed to a desire for cognition on the part of their readers.[21] Furthermore, more and more than engi started beingness composed in this period, with new emakimono flourishing in a manner beyond that of the Kamakura and Nanbokuchō periods.[21] Ichiko contends that these engi must be considered a special category of setsuwa.[21]

Toward the terminate of the medieval period, Arakida Moritake compiled his Moritake Zuihitsu (守武随筆).[21] The latter one-half of this work, titled "Accounts I Accept Heard in an Uncaring World" (心ならざる世中の聞書 Kokoro narazaru yononaka no bunsho), collects some 23 curt stories.[21] This piece of work is noted as a precursor to the literature of the early modern period.[21]

Late medieval diaries, travel literature and essays [edit]

The simply surviving diary by a court woman in this period was the Takemuki-ga-Ki (竹むきが記), written by Sukena's daughter (日野資名女 Hino Sukena no musume) during the Nanbokuchō flow.[21] A number of courtiers' Chinese diaries survive from this menstruation, including the Kanmon-nikki by Prince Sadafusa, the Sanetaka-kōki by Sanjōnishi Sanetaka, and the Tokitsune-kyōki by Yamashina Tokitsune.[21] The Sōchō Shuki (宗長手記), written by the renga chief Sōchō, is considered by Ichiko to be the only kana diary of this menstruation to accept literary merit.[21]

Saka Jūbutsu'southward (坂十仏) work Ise Daijingū Sankeiki (伊勢太神宮参詣記), an business relationship of a 1342 visit to the Ise Grand Shrine,[24] is one case of a genre of travel literature describing pilgrimages.[21] Other such works include the travel diaries of Gyōkō, a monk-poet who accompanied the shogun on a visit to Mount Fuji,[21] Sōkyū's Miyako no Tsuto (都のつと),[21] and Dōkō's Kaikoku Zakki (廻国雑記). [21] A neat many travel diaries by renga masters who travelled the state during this time of war, from Tsukushi no Michi no Ki (筑紫道) by Sōgi onward, also survive.[21] Some warriors of the armies sweeping the country toward the stop of the medieval period also left travel journals, including those of Hosokawa Yūsai and Kinoshita Chōshōshi.[21]

Not many zuihitsu survive from this menstruum, merely the works of poetic theory that were written by the waka poets and renga masters include some that could exist classified as essays.[21] The works of Shinkei, including Sasamegoto (ささめごと), Hitorigoto (ひとりごと) and Oi no Kurigoto (老のくりごと) are examples of such literary essays, and are noted for their deep grasp of the aesthetic principles of yūgen, en, hie, sabi, then on.[21]

Noh, kyōgen and kōwakamai [edit]

Drama is a major facet of Japanese literature in the medieval period.[21] From the Heian period on, entertainments such as sangaku , dengaku and sarugaku had been popular among the common people,[21] while temples hosted music and dance rituals, namely fūryū and ennen.[21] In the 14th and 15th centuries, Kan'ami and his son Zeami, artists in the Yamato sarugaku, tradition created noh (also chosen nōgaku), which drew on and superseded these precursor genres.[21] These men were able to accomplish this chore not but because of their ain skill and effort, but as well the tremendous favour shown to the burgeoning art grade by the Ashikaga shoguns.[21] Kan'ami and Zeami—specially the latter—were bully actors and playwrights, and pumped out noh libretti (called yōkyoku) one afterwards the next.[21]

Noh developed into a full-fledged art course during this menstruation.

Zeami also composed more than 20 works of noh theory, including Fūshi Kaden , Kakyō and Kyūi .[21] Ichiko calls these excellent works of artful and dramatic theory, which drew directly on Zeami's feel and personal genius.[21] Zeami's son-in-law Konparu Zenchiku inherited these writings, but his own works such as Rokurin Ichiro no Ki (六輪一露之記) show the influence of not only Zeami just of waka poetic theory and Zen.[21] Later on noh theorists like Kanze Kojirō Nobumitsu continued to develop on the ideas of Zeami and Zenchiku, and under the auspices of the warrior class, the nobility, and various temples and shrines the noh theatre continued to grow and expand its audition into the Edo flow.[21]

Closely related to noh, and performed alongside it, was kyōgen (likewise called noh-kyōgen).[21] Kyōgen was probable a development of sarugaku, but placed more emphasis on dialogue, and was humorous and often improvised.[21] At some time around the Nanbokuchō menstruation this genre split off from mainstream noh, and information technology became customary for a kyōgen functioning to be put on between ii noh plays.[21] The language of kyōgen became solidified to a certain extent past around the end of the Muromachi menstruum (mid-16th century).[21] According to Ichiko, while noh consists of song, trip the light fantastic, and instrumentals, is more "classical" and "symbolic", and is based on the ideal of yūgen, kyōgen relies more on spoken dialogue and movement, is more "contemporary" and "realistic", and emphasizes satire and humour.[21] Its language is more than colloquial and its plots more comedic.[21]

Kōwakamai developed somewhat later on than noh.[21] According to tradition, the form was established past Momoi Naoaki (桃井直詮),[21] a Nanbokuchō warrior's son whose infanthood proper noun was Kōwakamaru (幸若丸).[21] Kōwakamai were performed by low-form entertainers in the grounds of temples and shrines, as musical adaptations of the medieval war tales,[21] with their dances being straightforward and simple.[25] 51 libretti are extant,[26] including heiji-mono (平治物, works based on the Heiji Monogatari), heike-mono (平家物, works based on The Tale of the Heike), hōgan-mono (判官物, works about the tragic hero Minamoto no Yoshitsune), and soga-mono (曽我物, works based on the Soga Monogatari).[26] Such performances were obviously well-loved by members of the warrior course during the cluttered period of the belatedly 15th and 16th centuries, only went into decline in the Edo menses.[26]

Folk songs [edit]

While imayō , equally well as enkyoku (宴曲, or sōga/haya-uta 早歌) and wasan (Buddhist hymns), were popular in the early medieval menstruation, the later medieval period was dominated by sōga and the newly emerging ko-uta (小歌).[26] The representative collection of ko-uta is the 16th-century Kangin-shū , which includes a pick of sōga, songs to exist intoned and kōtai (小謡) songs from dengaku and sarugaku plays, arranged by genre, and more a few of its entries sing of the joys and sorrows of the common people of that time.[26] The Sōan Ko-uta Shū (宗安小歌集), compiled at the stop of the Muromachi menses, and the Ryūta Ko-uta Shū (隆達小歌集), compiled in the Azuchi–Momoyama menstruum or at the very get-go of the Edo menstruum, also collect ko-uta from this period.[26] The Taue-zōshi (田植草紙) records the farming songs sung past rice farmers during the religious rituals performed when planting their rice paddies.[26]

Kirishitan literature [edit]

For virtually a century after the inflow of Francis Xavier in Kagoshima in Tenbun eighteen (1549), Jesuit missionaries actively sought converts among the Japanese, and the literature these missionaries and Japanese Christian communities produced is known as Kirishitan Nanban literature (キリシタン南蛮文学 kirishitan-nanban bungaku).[26] This includes both translations of European literature and Christian religious literature produced in Nippon.[26] The Amakusa edition of The Tale of the Heike (天草本平家物語 Amakusa-bon Heike Monogatari), which translated the piece of work into the colloquial Japanese of the sixteenth century and represented it entirely in romanized Japanese, was printed in Bunroku ane (1592), and the following twelvemonth saw the printing of the Isoho Monogatari (伊曾保物語), a translation into vernacular Japanese of Aesop'south Fables that was similarly printed entirely in romanized Japanese.[26] Isoho Monogatari, because it was seen as a secular collection of moral fables, managed to survive the anti-Christian proscriptions of Tokugawa period, continuing to be printed in Nippon until at least 1659, with several handwritten copies likewise surviving.[27]

Cover of Arte da Lingoa de Iapam

The Jesuits as well published linguistic works such as the Portuguese-Japanese lexicon Vocabulário da Língua do Japão and João Rodrigues's Arte da Lingoa de Iapam, which were originally produced to aid in proselytizing activities, only have become of import resources for Japanese historical linguistics.[26] Other works included Dochirina Kirishitan, a Japanese edition of Doctrina Christiana that has been noted for its elementary, clear and straight employ of the Japanese vernacular.[26]

Ichiko notes that these works, which were all produced in the Azuchi–Momoyama and very early Edo periods, did not have a significant influence on medieval Japanese literature, but are nevertheless an important office of the history of Japanese idea at the end of the center ages.[26]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Some scholars view Yoshino Shūi as a forgery composed in the late Muromachi catamenia.[21]

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c d due east f thou h i j m fifty m n o p q r s t u v w ten y z aa ab air conditioning advertizement ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Ichiko 1983, p. 258.

- ^ Keene 1999, pp. 999–g.

- ^ Keene 1999, 689, note 73.

- ^ Keene 1999, 661.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 258–259.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j k fifty m due north o p q r s t u 5 due west ten y z aa ab ac advert ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Ichiko 1983, p. 259.

- ^ Keene 1999, p. 791.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 259–260.

- ^ a b c d e f grand h i j k l k due north o p q r s t u 5 w x y z aa ab air-conditioning ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar every bit at au av Ichiko 1983, p. 260.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 260–261; Keene 1999, p. 1062.

- ^ a b Ichiko 1983, p. 261; Keene 1999, p. 1063.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j k l thou n o p q r southward t u v w x y z aa ab ac advertizing ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar equally at au av aw Ichiko 1983, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Ichiko 1983, p. 261; Keene 1999, p. 1064.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, p. 261; Keene 1999, pp. 1063–1064.

- ^ a b Keene 1999, p. 1063.

- ^ Kidō 1994.

- ^ Keene 1999, pp. 1094–1097.

- ^ Keene 1999, p. 972.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j chiliad fifty thousand due north o p q r s t u 5 w ten y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar equally at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd exist bf bg bh bi Ichiko 1983, p. 262.

- ^ a b Keene 1999, p. 874.

- ^ Keene 1999, p. 907, note 21.

- ^ Nishiyama 1998.

- ^ Ichiko 1983, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j 1000 50 grand Ichiko 1983, p. 263.

- ^ Sakamaki 1994.

Works cited [edit]

- Ichiko, Teiji (1983). "Chūsei no bungaku". Nihon Koten Bungaku Daijiten 日本古典文学大辞典 (in Japanese). Vol. iv. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. pp. 258–263. OCLC 11917421.

- Nishiyama, Masaru (1998). "Ise Daijingū Sankeiki" 伊勢太神宮参詣記. World Encyclopedia (in Japanese). Heibonsha. Retrieved 2019-03-06 .

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Keene, Donald (1999) [1993]. A History of Japanese Literature, Vol. 1: Seeds in the Center – Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Tardily Sixteenth Century (paperback ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN978-0-231-11441-7.

- Kidō, Saizō (1994). "Nijō Yoshimoto" 二条良基. Encyclopedia Nipponica (in Japanese). Shogakukan. Retrieved 2019-07-15 .

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Sakamaki, Kōta (1994). "Isoho Monogatari" 伊曽保物語. Encyclopedia Nipponica (in Japanese). Shogakukan. Retrieved 2019-07-26 .

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

buffingtonpearouble.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_Japanese_literature

0 Response to "How Did Art and Literature Differ Between Europe and Japan?"

Post a Comment